The electricians at the Norwegian grid company Lede AS have gone fully digital. They still have to climb poles and make repairs but they save a lot of time by having access to all information via digital systems

Published in Europower Energi, January 20, 2021

Author: Haakon Barstad

(The article is translated from Norwegian by Trimble)

– Okay, we’re digital, but we still have to climb the pole. Are you going to climb or should I?

Electrician Thomas Storås looks at colleague Tor Olav Fjeldheim. It’s five degrees below zero and windy. It is probably not very tempting to climb up to the heights.

– I’ll climb, says Fjeldheim.

– Then I’ll be the RFW, says Storås.

The latter is electrician jargon. More on that later.

We are in the grid area of Lede AS, more specifically at Tjodalyng between Larvik and Sandefjord. A cottage by the sea has lost its power, and Storås and Fjeldheim have been sent out to find the fault.

While Tor Olav Fjeldheim puts on his climbing gear, Thomas Storås reports via the Trimble Utility To Go system that work is in progress. Photo: Haakon Barstad

However, the term "sent out" does not quite fit. Because like all other tasks they are working on, they have been assigned this task digitally via Utility To Go system.

All the electricians in Lede start their working day from home. This is not related to corona restrictions but standard procedure. The first thing they do in the morning is to check Utility To Go for tasks that have been assigned to them. In addition, they have access to a list of smaller tasks that are less urgent.

So let's go 30 minutes back in time. Storås is in the car and checks out the task related to the cottage with no electricity. The cottage is not in use during winter, so it’s not an urgent task, but the fault still needs to be fixed as soon as possible.

The electrician evaluates the tasks on the tablet and gets access to all relevant information. That's the whole point of this system. Access to all information everywhere, at all times.

Among other things, the electrician can read a report from the customer call. It was the grid company that discovered that the cottage did not have electricity and contacted the customer. The issue was discovered as the utility could not establish contact with the AMR meter.

– The customer has been to the cottage and inspected, but found no faults there. The fuses were intact, Storås reads.

He opens a map packed with information about all the poles, transformers and cables in the area.

– What this tool helps us with is planning the job before we leave for the task. For example, when I click on the map, I can see what kind of electricity line the customer point has. From what I see now, I imagine that there are faults on the clamping, he says.

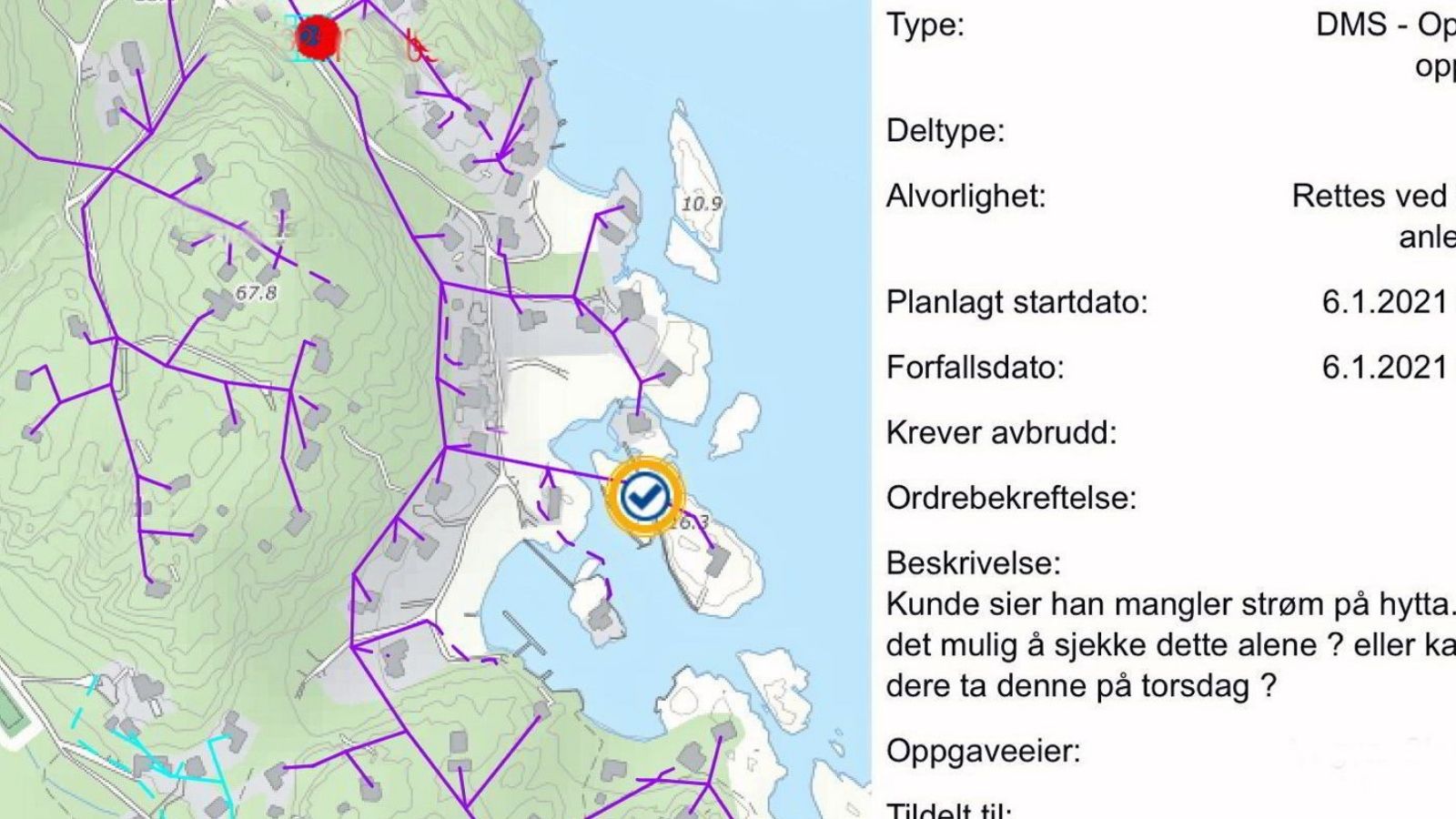

This is a screenshot from Utility To Go. The electricians can click on the details of all the grid-objects in the area. Europower has removed customer information and names. Photo: Lede AS.

He clicks further into the map and gets more details.

– I can try to ping the neighboring cottages, he says.

This means sending a signal to the AMR meters and see if they respond. The electrician can do this directly from the tablet. If no contact is made with any of the cottages, there are indications that the fault is not connected to the cottage without power.

– Hmmm, none of them are responding, that's strange. But this particular part of the system is not always completely stable. This scheme is quite new, so it happens that there are bugs, he says.

To check if the system is working, he pings the AMR meter at his own home in Larvik.

– Dead there too, then it's the pinging that's not working right now. It happens sometimes, but for the most part the system is very stable. Had I been told that several AMR meters did not respond, we would have started troubleshooting in a different way, he says.

He re-examines the map and pulls up a satellite photo.

– The cottage is located on an island right by the shore, but it doesn’t look like we need a boat. I see a bridge here, we can use that, he says.

In brief, the system gives the electrician access to all the information the grid company has available.

– For example, in this kind of cottage areas, there are some road barriers that need to be unlocked. When I click on the barrier we have to go through now, I am told that there is a key in the transformer station on the way in. So we can just stop there, pick up the key and avoid wasting time. It’s little things like this that save us a lot of time, and make us more efficient, says Storås.

Electrician Thomas Storås checks the details of the next assignment in the Utility To Go system. In the background his colleague Tor Olav Fjeldheim. Photo: Haakon Barstad

When Storås talks about the system, he is full of terms that ordinary people don’t use. There is rarely a sentence without the term POI in it.

– POIs are points of interest. If you look at the map, the POIs are marked. There are various tasks that need to be done. They have different priorities. If we don’t have urgent assignments and have free time, we take a POI nearby. When we click on the map, we see what the task is about, he says.

At the same time, colleague Fjeldheim arrives at the meeting place. Although the electricians always work in pairs, the Lede guys each have their own car.

– The fact that there are always more than one of us going on the assignment has to do with security. We could have done many of the jobs alone, but when you're climbing poles and working with electricity, you should not be alone, says Storås.

The only task they do alone is marking. When some object is not marked properly, it is tagged as a POI, and marking can be done by a single electrician.

– It is also very good to transport equipment with two cars, or if we have to pick something up, says Storås.

Lede covers power grids in about half of Telemark, the whole of Vestfold and also some of former Buskerud county.

It also has grids in the former Svelvik municipality which is now part of the Viken county.

– It would be cumbersome to have to go all the way to the central warehouse in Porsgrunn every time we need extra equipment. Therefore, 7–8 containers with equipment have been set up in strategic locations. Via a separate app provided by Elektroskandia, we can order and pick up the material we need to have, he says.

Arriving at the site, Thomas Storås (left) and Tor Olav Fjeldheim use their mobile phones to find the cottage in question. They have access to the entire system via their mobile phones. Photo: Haakon Barstad

They arrive at the cottage area. The key is in the transformer station as it should be, and they can unlock the barrier. When they have parked and got out in the cold, the electricians have to re-orient themselves to find out which cottage it is. Both pull out their mobile phones.

– We have access to exactly the same system on the mobile phone. It’s all web-based, there's no separate app. But it requires a lot of logging in, because there’s a lot of sensitive customer data in there, says Fjeldheim.

Using the map, they quickly locate the cottage, and start looking for faults. The first stop is the fuse box, which in this area sits on the outside wall of the cottage. The customer was right, the fuses are intact.

Then they check the aerial line. Nothing wrong close to the cottage wall, so they follow the line to the nearest pole. From the ground, they spot what is wrong.

– That’s what I said, one of the clamps is broken, says Storås.

They share the task between them. Fjeldheim says he can climb, while Storås is the RFW, which means he has the overall responsibility for the task. RFW stands for Responsible for work.

– Or Responsible for everything, says Fjeldheim and chuckles.

As the RFW, Storås records in the system what the fault was. He uses his mobile phone to do this. He gives a short description of what needs to be done and marks the POI as "work in progress".

The cottage is located on a small island, but on a satellite image in the system, the electricians had seen in advance that there was a bridge they could use. Thus, they did not have to bring a boat. Photo: Haakon Barstad

Then they go back to the cars to get equipment. But what happens? Fjeldheim pulls out a paper form.

– It’s an HSE form, it is still on paper. I expect that it will be added to the system soon, he says.

He writes by hand what they are going to do, what risks are involved in the task and what is being done to reduce risks.

– That’s all, now it's finished. Now the Responsible for everything can sign, says Fjeldheim.

(The HSE (Health, Safety and Environment) form is still paper based. – I expect that it will be added to the digital system soon, says Tor Olav Fjeldheim. Photo: Haakon Barstad)

He puts on his climbing gear and fills various bags with equipment. The clamp that must be replaced is in stock in the car.

– We have lots of stuff with us that is used frequently, but if we were to bring all possible cables and equipment, we would have to drive a semi-trailer, says Storås.

The two electricians walk back to the pole, and Fjeldheim begins his ascent. Pole climbing shoes, ropes, double safety ropes, helmet, and 1000 volt gloves. The new clamp must be installed while there is electricity in the wires.

– These are not dishwashing gloves he is wearing, the name already tells you how much such 1000 volt gloves can take. It’s only 230 volts into the cottage, says Responsible for everything, watching from the ground.

With orientation, troubleshooting and climbing, the task has so far taken less than an hour, but the actual job of changing the clamp has been done in less than a minute.

– But there is no app that can do this. Even though we are digital, we still have to climb poles and connect clamps, says Storås.

While Fjeldheim is still up in the air, Storås checks the fuse box.

– Now it’s back at full power, everything is fine, he shouts.

The colleague climbs down while Storås reflects on the benefits of being digital.

– We have to climb and connect and troubleshoot, that's our job. But the fact that we have access to all the information no matter where we are, makes us more efficient. We do not have to waste time finding information. We have everything in our pocket. Tasks, status, reporting, and practical info – everything is there, says Storås.

This also includes the next task. As soon as Fjeldheim is down from the pole, they check the tablets and drive off to the next POI.

No digital system can climb poles and repair broken clamps. Tor Olav Fjeldheim is on his way up in height to do what the job really is about. Photo: Haakon Barstad